The funeral of my friend Peter Bastian two days ago was not just a beautiful and comforting event, it was deeply challenging too. He had made sure it would be – as a final act of uncompromising love, I think. Peter was like that. Generous with good vibrations and enjoyable experiences, but also strong on the point of discipline and commitment in order for meaning and spirit to come through in life. Generous with that too, to the point of being a bit hard on friends and students sometimes.

Peter was a physicist, musician, meditation teacher and free-style lecturer on a lot of themes to do with the spirit of our time. None of this was done with less that full energy and existential commitment, and all of it shot through with ongoing philosophical investigation – in the full sense (a sense I try to define elsewhere in this blog).

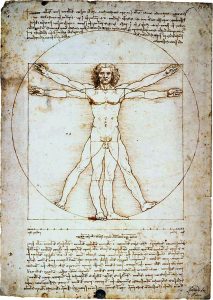

The idea of the renaissance man – the human being unfolding its natural light freely in all directions, drawing from the deep wells of genius and educated by the full scope of classical science and art – this beautiful renaissance idea of human flourishing has gained new popularity in recent years. Perhaps the idea of “rennaisance man” has watered down to signifying any juxtaposition of several educations and interests, making it very trivially true of Peter Bastian and almost meaningless to mention.

Peter was a renaissance man in a stronger sense. He threw dedicated, disciplined effort into all the fields he touched, and just like Leonardo and the others he did so with a spiritual agenda – trying to turn all these engagements into dialogues between higher meaning and solid embodied practice.

A main work of his is the 1987 bestseller Ind i musikken (“Into Music” – curiously it has not yet been published in English but it exists in Japanese). It is an exploration of the phenomenon of flow, mainly exemplified in music listening, performance and improvisation. On top of that I would say the book develops and employs an approach of pragmatic phenomenology, suited to follow and inspire a free and creative but dedicated training effort. It has become a guidebook for a generation of musicians and many others who identify with being a free musical spirit or something like that. My son Asbjørn – currently a conservatory student and active in several bands – considers Peter’s book a “bible” and decided to come with me to the flow master’s funeral.

But Peter’s work was not all about musical or music-like flow. In fact he was somewhat disappointed with the idea or practice of flow when I first began to know him and philosophize with him 15 years ago. He considered it a distraction from what he now saw as main spiritual practice: meditation, meditation retreats and the development of meditation-based groups. For Peter, this was tied to a strong involvement with a spiritual teacher, Andrew Cohen, and his organization. My lifelong meditative engagement in other organizational/traditional “packages” (Tibetan Buddhist and others) meant that we had a large field of partly shared and partly different experiences to co-philosophize in. We also shared a realization that spiritual practices need not only physical but also social bodies – and that it is important to develop modern ways of sharing spiritual inspiration and guidance, beyond the closedness of classical authoritarian forms but without losing the dedication to effort, authenticity and “quality “- whatever quality may be or become here.

Years later Peter took further steps, leaving the organization of Andrew Cohen and also going beyond his de-facto denouncement of flow and music. I think it is fair to say that his final position was one in which his two former fields of focus – flow, and pure awareness – became channels or background something wilder that might be called spirit or living embodied wakefulness. “Final position” of course needs to be taken in a relative sense, Peter was really not really a man of position, rather one of ongoing, dedicated transcending movement.

Peter’s engagement in social embodiment of spirituality was pivotal throughout the years I knew him. A phrase he often used to point to this was “creative collectives”, clearly meaning not just innovation, not even just innovation with success and impact, but innovation expressing or even creating something deep in the situation – something that discovers and expresses higher orders, purposes, chords, grooves. To be truly creative together, a group needs to be in a contemplative space together – or even to BE a shared meditative awareness.

Creativity was so fundamental to Peter that he talked of it as omnipresent, not reserved for humans, or even an expanded humanoid sphere including human collectives and perhaps God or gods. He embraced the idea of a creative or evolutionary cosmos put forward by process thinkers such as Whitehead and popularized by Wilber and Peter’s teacher Cohen. Process, autopoiesis, self-organizing systems, all the way down. But for Peter it was crucial that this kind of non-modern or post-modern cosmological vision doesn’t collapse into flat lazy easy harmonies, but rises vertically into commitment and generosity.

The very last exchange I had with Peter, two weeks ago, was about exactly this point of vertical commitment – but also about something beyond that, a soft dimension of love and grace. We talked about the cosmos being not only creative but also radically unfinished, so that in a sense the Christian God – that had become a strong resonance for Peter in his final years – is not the mighty but the little one, one who needs care and looking after. One about whom it may even make sense to say, as they do in the orthodox tradition, that there is a “God’s Mother”.

In any case, for Peter, the renaissance man, there was nothing that wasn’t a musical instrument (see top picture). Also, nothing was not an occasion for philosophical process of wisdom – even his own disease and dying.

Next time I met him was at the funeral.

We were many, perhaps 200 of us – family, friends, musical-spiritual-philosophical fellows – in the old monastery church at Løgumkloster. The beauty of medieval buildings echoing a world of simple faith, the light and air of the first real spring day, the gathering of soft-spoken resourceful people in gentle grief – everything pointed to a gentle event of comfort and conciliation.

Except Peter’s intention. When the soft silence had settled in, what he had in store for us was not gentle tones or words. It was a sudden burst of unsentimental, almost violent organ music. Ten minutes of catastrophic breakthroughs on an unstable edge of dissolving dissonance and breaking harmonies. Olivier Messiaen’s Apparitions de l’Eglise Eternelle. (Listen to it here if you dare, it needs to be loud from the beginning and followed all the way). Nothing to relax into here, not even orthodox religious doom or classical nonreligious existentialist meaninglesness, this is the unresting position of unfinished work with infinite tallness of striving.

Of course the day was also enjoyable, with many beautiful people sharing memories and gratitudes of a beautiful human being. He just wouldn’t leave us without a final push into the radical project of creation.

–

Honored be his memory – except that this misses the point. So let’s try something else:

Played on be his music, exalted be his discipline, continued be his dionysiac-apollonian explorations, growing be his uncompromising love, blessed be his wild spirit.